Это НЕ история любви!

Авторка: Адина Маринцеа

Близость анархизма и панка не случайна, у них есть определенные общие принципы, которые привели к образованию музыкально-политического гибрида под названием «анархо-панк». Восстание, этика «DIY» («сделай сам»), экономическая и социальная самоорганизация или борьба за власть - это политические и милитантные принципы, которые определяют анархо-панк-движение.

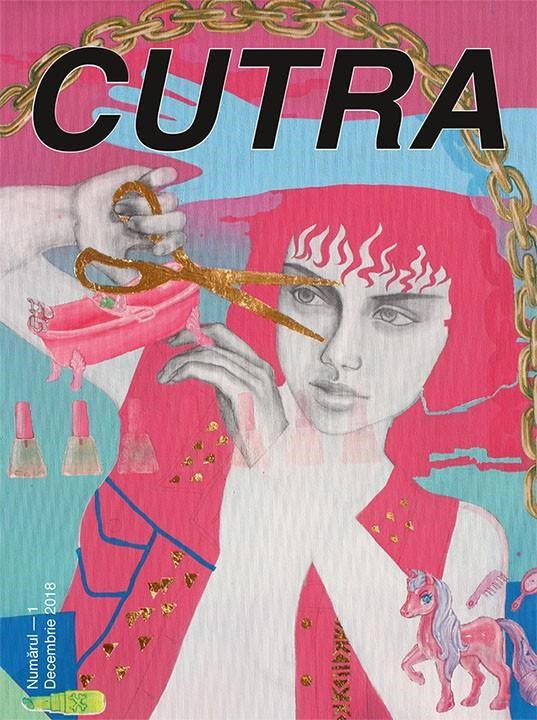

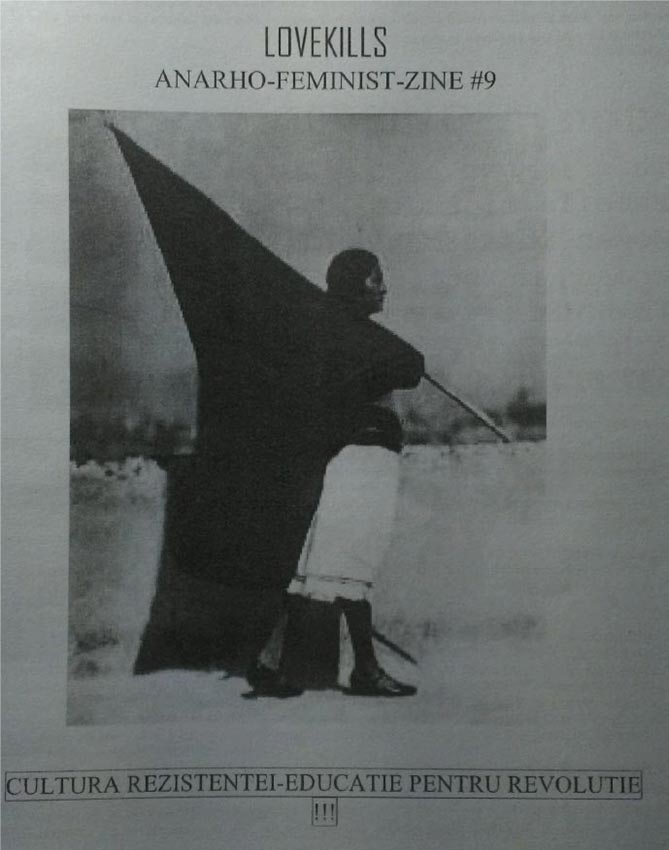

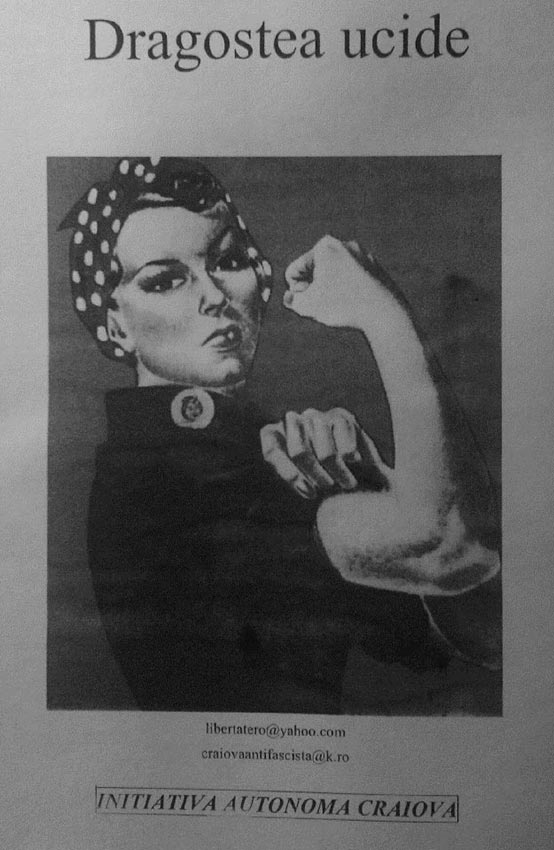

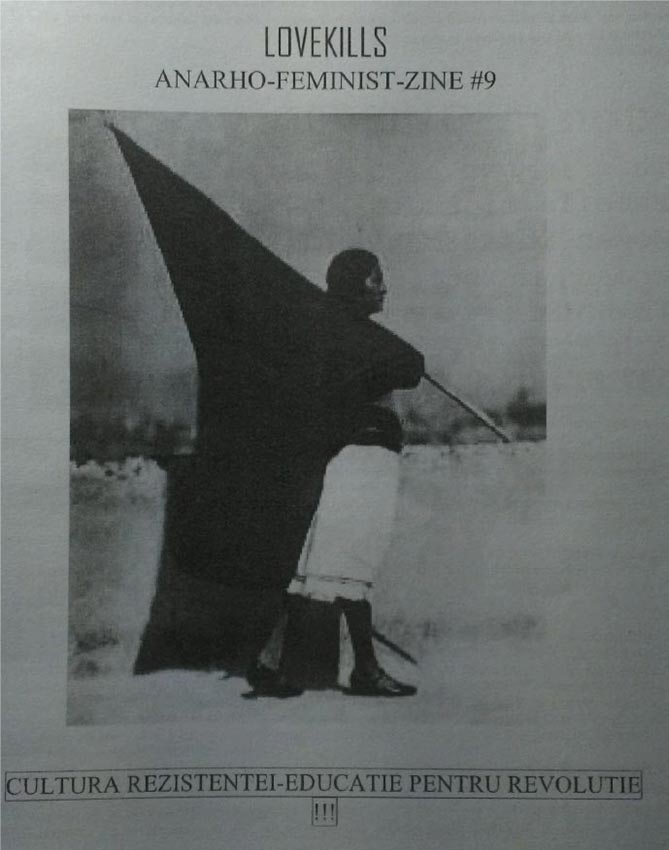

LoveKills: Это НЕ история любви!

Почему LoveKills? Любовь убивает - это правда, признанная вокруг нас. Где бы ни возникала любовь, за ней следуют ненависть, ревность, принуждение. Большая часть ограничений свобод и возможностей совершается во имя любви. Большинство преступлений совершается из-за любви. Родители избивают своих детей, потому что любят их и желают им всего наилучшего. Государство ведет войны за благополучие своего народа, чтобы защитить его. Государство и церковь применяют законы против абортов для сохранения нации и из любви к еще не родившимся. Патриархатный строй, полный ненависти и мести, превратил любовь в самое ужасное чувство, в чувство слабости. Таким образом, женщина олицетворяет любовь - она воплощает любовь. Женщина призывает своих сыновей пойти на войну и полюбить свою страну. Именно женщина из любви к дочери призывает ее выйти замуж, чтобы обеспечить ее будущее. Женщина - это та, кто ранит свое тело в пользу государства. Женщина - это та, которая из-за слишком большой любви поддерживает статус-кво, хотя только она может его изменить. Женщина может менять систему, думая о себе, ведя борьбу за личную свободу. Любовь убивает в системе, основанной на ненависти; любовь - это извращенное чувство, которому не место в этом мире. - Интервью с LoveKills, 2009 г.[6]

Что нас определило? Куда бы мы ни повернули голову, мы увидели патриархатную культуру, - я думаю, это определяло нас, социальный контекст того времени.

[…]

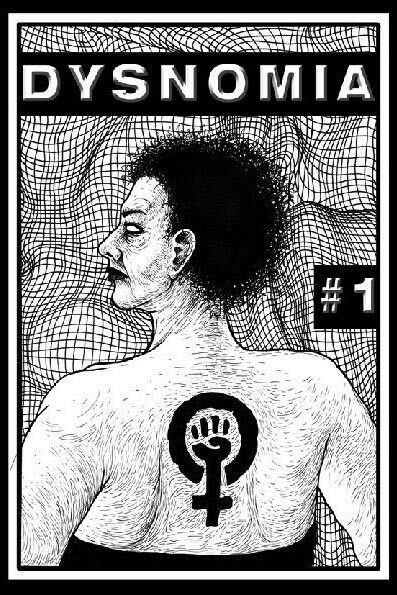

Первым появился фанзин, а не коллектив - в 2003 году, его написала ***[7], которая уже писала для других анархистских изданий, в которых были парни. Тот факт, что девушка начала публиковать анархо-панк-фанзин, в котором панк-девушка была очень заметна и обсуждались сексизм и патриархат, сильно встревожил мачо-панк-сцену в Крайове. Из-за этого панк-сцена там раскололась, и затем стали появляться всевозможные проблемы, конфликты, насилие между группами, - то есть активная группа, которая воюет, и другие панки. Каким-то образом из солидарности и из-за всех этих событий мы присоединились к ее работе, и я, и ***, это то, что мы помним, и я думаю, что мы назвали себя коллективом, когда решили организовывать фестивали. До этого это был просто фанзин LoveKills.

ФЕМИНИЗМ: сложные отношения

Коллектив LoveKills - это анархо-феминистский проект, поэтому его направление больше склоняется в сторону DIY, чем в сторону феминизма третьей волны, хотя этика DIY считается его частью. Теоретически мы, конечно, феминистки, но, по нашему опыту, феминизм, с которым мы столкнулись, особенно в Румынии (что-то вроде феминизма второй волны), на самом деле является чем-то, что мы отвергаем, поскольку мы видим это как нечто, усиливающее бинарность гендера и доминирование.

Например, нынешний феминизм в Румынии во многом связан с православной церковью и идет рука об руку с ортодоксально-христианской моралью. Такой логикой он явно подрывает репродуктивные права женщин, - права, которые были восстановлены в начале 90-х, после десятилетий диктатуры. Он также побуждает женщину благочестиво подчиняться патриархальному образцу семьи (абсолютная ценность румынского общества). Эмансипированная женщина для этих феминисток - женщина-менеджер / политик / президент, уделяющая большое внимание близости к православию. Мы, конечно, против такой эмансипации, потому что призываем бойкотировать выборы и бороться против любой иерархической структуры. Третья волна очень мало представлена в румынском контексте.

Основная идея нашей работы и главный фокус - анархизм. Мы связываем феминизм с анархизмом, поскольку видим, что есть еще проблемы с сексизмом и доминированием в «свободной» и «дружественной» среде, так называемых анархистских медиумах. Но мы делаем больший упор на анархизм, поскольку считаем его подходящим способом достижения абсолютной свободы всех существ. - Интервью с LoveKills, 2009 год[8].

Мы не объявляли себя феминистками ни тогда, ни при каких обстоятельствах, ни впоследствии, ни позже, ни в настоящее время. […] Не вписываться в феминизм, не соглашаться с ним, не верить феминизму как решению, не означает, что вы антифеминистка. Я имею в виду, что феминизм для меня вообще не говорит о государстве, он вообще не доходит до корня, где проблема. Я не думаю, что феминизм помогает, но я НЕ объявляю себя антифеминисткой. Я всегда очевидно была анархисткой.

Как тогда воспринимался феминизм? В анархистской сцене было довольно сложно говорить об анархо-феминизме, либо феминизм не присутствовал в дискуссиях, во всяком случае среди анархистов - ни анархо-феминизм, ни феминизм, ни какая-либо борьба с сексизмом. В то время это была острая тема.

Солидарность и взаимопомощь

В то время распространение зинов происходило во всех городах, где были панки, активист_ки, анархист_ки, концерты. Группы или активные люди сотрудничали друг с другом, мы сотрудничали, и у всех нас были брошюры, журналы, листовки повсюду. Если бы что-то произошло в Крайове, я бы сделала листовку против фашизма, Noua Dreaptă (Новых Правых), мы бы нашли способ распространять их, будь то в день их приезда или на этой неделе, везде, в других городах, где были люди. Если в Яссах что-то делали с животными, все делились этим флаером. Вот как это делалось. Нет, никто вас не принуждал, но это была солидарность. Так как нас было немного, лучше было делиться везде. Вот как это было тогда. Была такая солидарность, и мы помогали друг другу.

Есть анархисты или люди в целом, с которыми вы ладите или не ладите. С разных точек зрения. Мы не делили их тогда на парней и девушек, не разделяем и сейчас. И тогда девочки и мальчики были одинаково патриархатными и сексистскими. Мы все жертвы одной и той же системы, патриархата, за исключением того, что женщины - двойные жертвы, они находятся под властью как мужчины, так и системы. Но нет, у нас ни в коем случае не было того, что они мальчики ... Напротив, у нас были мальчики, которые помогали нам, когда мы начали объединяться, чтобы быть фестивалем, у нас было много мальчиков, которые помогали нам, и куча девушек, которые выгнали нас…

Деморализация, трансформации и энергичное возвращение

В какой-то момент, я думаю, на третьем фестивале, каким-то образом двое из нас переехали в другие страны, Германию и Италию, и как-то стало сложнее с общением, также не хватало времени и все такое, и мы не продолжали.

Да, то, что произошло в контексте саммита НАТО, я могу сказать, что оно разрушило все движение, анархистскую сцену, левых, если было что-то вроде левой сцены, - это уничтожило все это, а потом все снова появилось с большим трудом. Я думаю, что новое появление началось, когда возникло движение Roşia Montană. И да, оно разорвало любые связи, повлияло...контроль, который был тогда и в дни до, и то, что произошло после, полицейский контроль ... принес много душевных проблем или страха, паники, всякого рода вещей, из-за которых людям было трудно начать все сначала.

Как вы смотрите на тот период? Изменилось ли что-нибудь фундаментальное в вашей идеологической позиции в отношении анархизма, феминизма, капитализма, социализма?

Анархизм был построен, я бы сказал, более прочно. Я бы добавила к капитализму фашизм. На данный момент я не рассматриваю их как отдельные, я думаю, что мы живем в самой фашистской форме капитализма или что это самый капиталистический глобальный фашизм всех времен. Не знаю, они перепутаны, я их больше не вижу по отдельности. Я никогда не беспокоилась о социализме и феминизме, я не верю в это, это как перевязка для раны капитализма или раны патриархата, мы просто не идем к корням проблем. Кладём это туда, чтобы не было видно раны, но не доберемся до корня. Чтобы меня не неправильно поняли, в то же время я солидарна со всей борьбой, восстанием, сопротивлением всех женщин повсюду, независимо от того, чему они верят или во что верят. Я меньше верю в неолиберальный феминизм.

Сегодня в Румынии по крайней мере два все еще действующих проекта по документированию и восстановлению румынской анархической истории: Editura Pagini Libere и ANARHIVA. На сайте ANARHIVA я нашла сканы большинства выпусков LoveKills, а также листовок или брошюр, выпущенных другими анархо-панк-группами того периода. До недавнего времени Равна (Râvna) также была очень активна в издательской деятельности. Это одна из самых долгоживущих анархистских групп, их веб-сайт был активен в период с 2010 по 2018 год.

Феминистские соцчастия, исторические (не)связности и (не)преемственности

This is (NOT) a love story!

The historical context in Romania makes it so that the pre-communist anarchist literature and activity, which is quite prolific[1], has remained largely unknown. The repressive national-communist regime either drove out the anarchists or silenced them, so that it was only in the early 1990s that an anarchist movement began to coagulate again, thanks to the punk scene. Internationally, punk rock emerged in the 1970s. In Romania, the punk scene developed in the 1990s, especially in Craiova and Timişoara, influenced by relations with the former Yugoslavia (especially Serbia). Punk groups and movements have existed since the 1980s, for example in more isolated areas on the outskirts of Timişoara[2].

The affinity between anarchism and punk is not a coincidence, they have in common certain principles that led to the formation of the musical-political hybrid called "anarcho-punk". Rebellion, Do It Yourself (DIY) ethics, economic and social self-organization, or the contestation of authority are political and militant principles that define the anarcho-punk movement.

LoveKills: This is (NOT) a love story!

Why LoveKills? Love kills – it is the truth recognized around ourselves. Wherever love emerges, it is followed by hate, jealousy, constraint. A great part of restrictions of freedoms and liberties are done in the name of love. Most of the crimes are done out of love. Parents are beating up their children because they love them and they wish the best for them. The State is leading wars for the wellbeing of its people, to protect them. State and Church are enforcing laws against abortion for the continuation of the nation and out of love for the yet unborn ones. The patriarchal system, full of hate and revenge, has transformed love into the most terrible feeling, into a feeling of weakness. This way, the woman represents love – she is embodying love. The woman is urging her sons to go to war and to love their country. The woman is the one, who out of love for her daughter, urges her to marry in order to assure her future. The woman is the one who is scarifying her body for the State. The woman is the one who, out of too much love, is maintaining the status quo, although only she is able to change it. The woman can change the system, thinking of herself, wearing a fight for the individual freedom.

Love kills in a system based on hatred; love is a perverted feeling, that doesn’t belong in this world. – Interview with LoveKills from 2009[6]

What determined us? In any direction we turned our heads, we saw the patriarchal culture, I think that determined us, the social context of that time.

[…]

The first one that appeared was the fanzine, not the collective, in 2003, it was written by ***[7] who was already writing in other anarchist publications in which there were guys. The fact that a girl started publishing an anarcho-punk fanzine in which the punk girl was very prominent and there was talk about sexism and patriarchy disturbed the macho-punk scene in Craiova a lot. Because of this, the punk scene there split up and then all sorts of problems, conflicts, violence between groups began to appear, ie the active group that militated and the other punks. Somehow out of solidarity and all these events, we joined her work, both myself and ***, this is what we remember, and I think we called ourselves a collective once we decided to organize festivals. Until then, it was just LoveKills fanzine.

FEMINISM: in a complicated relationship

LoveKills Collective is an anarcha-feminist project, so the direction would be more towards DIY and not so much towards third wave feminism, although DIY ethics is considered to be part of it. Theoretically we are feminists of course, but in our experience the feminism we came across, especially in Romania (a sort of second wave feminism), is something that we are actually opposing or rejecting, as we see it like something that re-enforces the gender binary and domination.

For example the feminism nowadays in Romania is much related to the Orthodox Church and goes hand in hand with orthodox-Christian morality. By this logic, it is obviously undermining women’s reproductive rights, rights that have been regained in the beginning of 90s, after decades of dictatorship. It is also urging the woman to piously submit to the patriarchal pattern of family (absolute value of Romanian society). The emancipated woman for these feminists is the manager / politician / president woman with a major focus on orthodox affinity. We are of course opposing such emancipation since we are calling for boycotting the elections and fighting against any sort of hierarchical structure. The third wave is very little represented in the Romanian context.

The main idea of our work and the main focus is anarchism. We attach feminism to anarchism as we see that there are still issues to deal with, regarding sexism and domination in the “free” and “friendly” environments, the so-called anarchist mediums. But anarchism is more stressed as we consider it to be the pertinent way to achieve the absolute freedom of all beings. – LoveKills interview from 2009[8]

We did not declare ourselves feminists then, under any circumstances, and neither afterwards, nor later, nor at this time. […] Not fitting into feminism, not agreeing with it, not believing in feminism that it is a solution, does not mean that you are anti-feminist. I mean, feminism for me doesn't talk about the state at all, it doesn't go to the root at all, where the problem is. I don't think feminism helps, but I do NOT declare myself anti-feminist. I was clearly an anarchist.

How was feminism perceived then? It was quite difficult in the anarchist scene to talk about anarcho-feminism, or feminism had no place in the discussion among people, in any case among anarchists in general - neither anarcho-feminism, nor feminism, nor any struggle against sexism. It was a mined subject at the time.

Solidaritaty and mutual aid

There are anarchists or people in general that you do or don't get along with. From different points of view. We didn't divide them into guys and girls back then, and we don't divide them like that now either. And back then girls and boys were equally patriarchal and sexist. We are all victims of the same system, the patriarchy, except that women are double victims, they are under the domination of both the man and the system. But no, by no means did we have this thing that they are boys ... On the contrary, we had boys who helped us, after we started to become a collective, to be a festival, we had the involvement of many boys who helped us, and a bunch of girls who kicked us out ...

Demoralizations, transformations and energetic comebacks

At one point, I think at the third festival, somehow two of us moved to other countries, Germany, Italy, somehow it was harder with communication, there was also a lack of time, and all that, and we didn’t continue.

Yes, what happened in the context of the NATO summit I can say that it destroyed the whole movement, the anarchist scene, the left, if there was something of a leftist scene, but it destroyed all of it and afterwards it re-appeared very hard, I can say that a reappearance of it was formed when the Roşia Montană movement emerged, and yes, it broke any connection, it had an impact ... the control that was then and in the days before and what happened after, the police control ... brought a lot of mental problems or fear, panic, all sorts of things that made it hard for people to have the strength to start over.

How do you look at that period? Has anything fundamental changed in your ideological position on anarchism, feminism, capitalism, socialism?

Anarchism was built, I might say, more solidly. I would add fascism to capitalism. At the moment I don't see them as separate, I think we are living the most fascist form of capitalism or it is the most capitalist global fascism of all time. I don't know, they're mixed up, I can't see them separately anymore. I have never bothered with socialism and with feminism as well, I don't believe in it, it's like a bandage to the wound of capitalism or not, to the wound of patriarchy, we just don't go to the root. We put it there so that the wound is not visible but we don’t go to the root. Not to be misunderstood, at the same time I stand in solidarity with all the struggles, revolts, resistance of all women everywhere, no matter what they believe, or in what they believe. I believe less in neoliberal feminism.

There are today in Romania at least two still active projects for documenting and recovering the Romanian anarchist history: Editura Pagini Libere and ANARHIVA. On the ANARHIVA website I found scanned most of the issues in LoveKills, as well as other flyers or brochures produced by other anarcho-punk groups from that period. Until recently, Râvna was also very active in publishing - one of the longest-lived anarchist groups, their website being active between 2010-2018.

Feminist complicities, historical (de)connections and (dis)continuities

Source: URL