Язык / Language:

Russian / Русский

English

Александр Муртазаев - выпускник исторического факультета университета Erasmus University Rotterdam, крымский татарин по отцу. Телеграм: @swellfella.

Симор Незорий - бакалавр философии, студент-график в Киеве. Инстаграм: @nezoriy.

tags: Деколонизация, Ислам, Исследования, Коренные народы, Расизм, СССР, Украина

История крымских татар, как и многих других национальностей постсоветского пространства, — история, во многом, недоговорок и боли. Депортация крымских татар из Крыма в 1944 году через семьдесят лет в Украине была признана геноцидом. Это событие разделило жизнь народа на до и после. Борьба людей за право вернуться домой продолжалась вплоть до девяностых. Многие активисты до сих пор продолжают работать с этой проблемой. Депортация и последующая разбросанность семей, десятилетиями формировавшихся сообществ и даже субэтносов привели к потере огромного числа ценных исторических материалов и доступа к устной культуре и семейным историям. Советские власти постарались, чтобы перекроить исторический нарратив под себя. Наконец, особую политизированность история крымских татар неизбежно приобрела после присоединения полуострова к России в 2014 году.

В таких условиях исследование национальной истории или истории инакомыслия выходит за рамки академизма и превращается в часть движения, которое возвращает своему народу право на скорбь, голос и идентичность, а вместе — на национальную историю. Историк, занимающийся такими темами, нередко оказывается в позиции, где необходим пересмотр традиционных идей об исследовательской объективности. Сейчас, когда продолжается вытеснение и искажение правды об истории крымских татар и репрессий против них, трудно четко определить конец исторической науки и начало политики, активизма и даже правозащиты.

В таких условиях исследование национальной истории или истории инакомыслия выходит за рамки академизма и превращается в часть движения, которое возвращает своему народу право на скорбь, голос и идентичность, а вместе — на национальную историю. Историк, занимающийся такими темами, нередко оказывается в позиции, где необходим пересмотр традиционных идей об исследовательской объективности. Сейчас, когда продолжается вытеснение и искажение правды об истории крымских татар и репрессий против них, трудно четко определить конец исторической науки и начало политики, активизма и даже правозащиты.

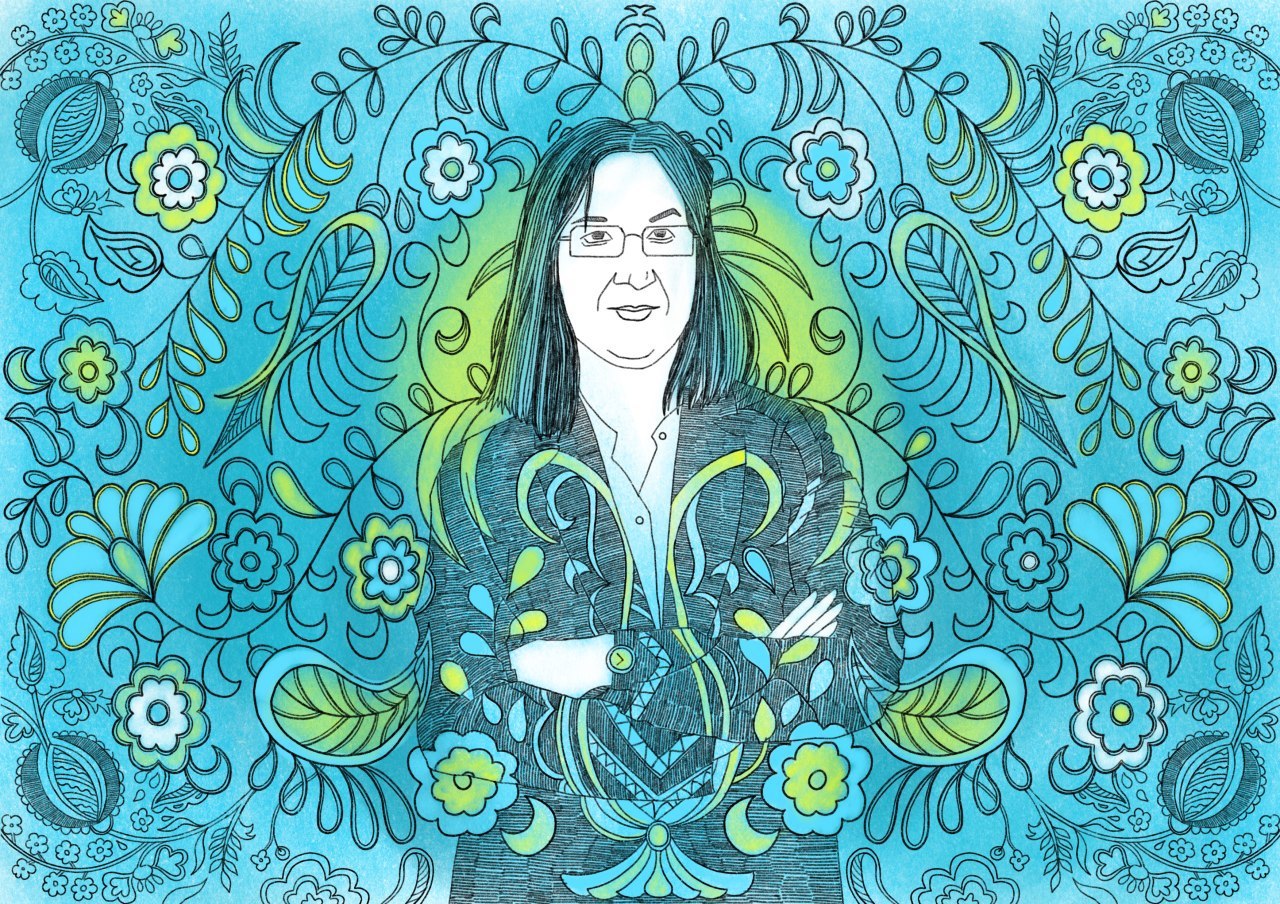

Гульнара Бекирова работает на пересечении этих областей всю свою долгую карьеру историкессы. Список всех ее научных публикаций, появлений на радио и телевидении, случаев сотрудничества с дружественными организациями и тому подобного занял бы три таких статьи, но все равно не передал бы по-настоящему огромного масштаба деятельности исследовательницы. В практике Бекировой, признанной экспертки по истории Крыма, можно выделить несколько ключевых исследовательских направлений: первое — национальное движение крымских татар, его зарождение, развитие, особенности и принципы; второе — депортация крымскотатарского народа, ее причины, геноцидный характер и разрушительные последствия.

Родители Гульнары, Тасим и Касиде Бекировы, были родом из Байдар и Керчи. В 1967 году они поселились в Мелитополе, где через год у них родилась Гульнара. Ни Тасим, ни Касиде не смогли вернуться в родные села после депортации из Крыма — Байдары были частью закрытой территории, недоступной для крымских татар, а их родная деревня Аджименды под Керчью была разрушена.

Бекирова вспоминала, что в школе история ее не интересовала. Куда больше ее привлекали живопись или художественная литература. Гульнара даже пробовала поступить в Харьковское художественное училище, но передумала и забрала документы. Выбрать для себя будущую профессию Бекирова смогла не сразу. После окончания школы она даже работала машинисткой на Мелитопольском моторном заводе, таким образом давая себе время подумать. Среди ее планов были филфак и режиссерский факультет ВГИКа, затем две неудачные попытки поступить на классическое отделение Ленинградского университета, недобор баллов на исторический факультет МГУ. Наконец, в августе 1989 года Гульнара поступила в Московский Историко-архивный институт РГГУ и закончила его в 1994 году со специальностью историка-архивиста. В 2003 году она была принята в члены НИПЦ «Мемориал», с которым была в контакте как минимум с 1996 года (если не раньше). Это случилось после публикации ее статьи «Проблема эмиграций крымских татар в российской исторической литературе» в сборнике «Корни травы», созданном при поддержке Фонда Генриха Белля и «Мемориала». Быть членом «Мемориала» Бекирова перестала уже после 2008 года, довольно богатого для неё на события: в этом году она начала работу на кафедре историко-филологического факультета Крымского инженерно-педагогического университета, начала вести свою еженедельную программу «Тарих седасы» («Отзвуки прошлого») на крымскотатарском телеканале ATR, где рассказывала о важных событиях и личностях в истории крымских татар. Другая программа на ATR, которую ведет Бекирова — «Тарих левхалари» («Страницы истории»).

С 2012 года Гульнара — кандидатка политических наук. Свою степень она защитила в Институте политических и этнополитических исследований им. И.Ф. Кураса НАН Украины. В интервью еженедельнику «Полуостров» 2006 года она отметила, что защита диссертации не была для нее важной стадией развития карьеры, и стимула в ней она не чувствовала. «Для меня важнее суть, содержание, а не форма. То есть моя работа», — говорила Бекирова. (Интересно, что это интервью у нее брал бывший тогда редактором «Полуострова» Васви Абдураимов, сейчас председатель крымскотатарской организации «Милли фирка» — политического оппонента Меджлиса крымских татар, с которым сотрудничает Бекирова). Это заметно: в достаточно долгий период между выпуском из университета и получением кандидатской степени Гульнара успела сделать себе имя как историкесса, опубликовать множество статей и монографий, принять участие в исследовательских проектах и телепередачах и получить Международную премию им. Б. Чобан-Заде, которой отмечают выдающиеся гуманитарные исследования по теме Крыма и художественные произведения на крымскотатарском языке.

Родители Гульнары, Тасим и Касиде Бекировы, были родом из Байдар и Керчи. В 1967 году они поселились в Мелитополе, где через год у них родилась Гульнара. Ни Тасим, ни Касиде не смогли вернуться в родные села после депортации из Крыма — Байдары были частью закрытой территории, недоступной для крымских татар, а их родная деревня Аджименды под Керчью была разрушена.

Бекирова вспоминала, что в школе история ее не интересовала. Куда больше ее привлекали живопись или художественная литература. Гульнара даже пробовала поступить в Харьковское художественное училище, но передумала и забрала документы. Выбрать для себя будущую профессию Бекирова смогла не сразу. После окончания школы она даже работала машинисткой на Мелитопольском моторном заводе, таким образом давая себе время подумать. Среди ее планов были филфак и режиссерский факультет ВГИКа, затем две неудачные попытки поступить на классическое отделение Ленинградского университета, недобор баллов на исторический факультет МГУ. Наконец, в августе 1989 года Гульнара поступила в Московский Историко-архивный институт РГГУ и закончила его в 1994 году со специальностью историка-архивиста. В 2003 году она была принята в члены НИПЦ «Мемориал», с которым была в контакте как минимум с 1996 года (если не раньше). Это случилось после публикации ее статьи «Проблема эмиграций крымских татар в российской исторической литературе» в сборнике «Корни травы», созданном при поддержке Фонда Генриха Белля и «Мемориала». Быть членом «Мемориала» Бекирова перестала уже после 2008 года, довольно богатого для неё на события: в этом году она начала работу на кафедре историко-филологического факультета Крымского инженерно-педагогического университета, начала вести свою еженедельную программу «Тарих седасы» («Отзвуки прошлого») на крымскотатарском телеканале ATR, где рассказывала о важных событиях и личностях в истории крымских татар. Другая программа на ATR, которую ведет Бекирова — «Тарих левхалари» («Страницы истории»).

С 2012 года Гульнара — кандидатка политических наук. Свою степень она защитила в Институте политических и этнополитических исследований им. И.Ф. Кураса НАН Украины. В интервью еженедельнику «Полуостров» 2006 года она отметила, что защита диссертации не была для нее важной стадией развития карьеры, и стимула в ней она не чувствовала. «Для меня важнее суть, содержание, а не форма. То есть моя работа», — говорила Бекирова. (Интересно, что это интервью у нее брал бывший тогда редактором «Полуострова» Васви Абдураимов, сейчас председатель крымскотатарской организации «Милли фирка» — политического оппонента Меджлиса крымских татар, с которым сотрудничает Бекирова). Это заметно: в достаточно долгий период между выпуском из университета и получением кандидатской степени Гульнара успела сделать себе имя как историкесса, опубликовать множество статей и монографий, принять участие в исследовательских проектах и телепередачах и получить Международную премию им. Б. Чобан-Заде, которой отмечают выдающиеся гуманитарные исследования по теме Крыма и художественные произведения на крымскотатарском языке.

Аннексия Крымского полуострова Россией повлияла на жизнь Бекировой, как и на жизни многих других крымских татар. Какое-то время после тех событий Гульнара еще преподавала в крымском университете, однако сейчас она уже не живет в Крыму. С 2014 года Гульнара ведет колонку «Страницы крымской истории» на сайте Крым.Реалии, состоит в украинском ПЕН-центре. С 2016 года Бекирова является заместительницей председателя комиссии Курултая крымскотатарского народа по изучению геноцида крымских татар и помогает прокуратуре Автономной Республики Крым в расследовании производства по факту геноцида, находя нужные документы и делясь уже известными ей источниками. Это расследование — довольно сложная задача, так как украинское законодательство не гармонизировано со стандартами международного права, определяющими военные преступления.

После аннексии Гульнара много путешествует по Украине, посещая конференции и читая открытые лекции об истории Крыма и крымских татар. Бекирова рассказывает, что благодаря аннексии она узнала о красоте и разнообразии Украины как страны. В последние годы она все больше занимается исследованием и популяризацией общей истории крымских татар и украинцев и их совместной борьбы с советским режимом.

В одном из своих интервью Бекирова отмечала, что звание профессионального историка «предполагает объективность и поиск исторической правды вне зависимости от национальной принадлежности». Она и сама при этом признает, что она — не только историк, но и крымская татарка, чья семья до сих пор не вернулась домой, и полное отстранение от политики или национального самосознания в таком случае невозможно. Как должна работать объективность исследователя, который занимается преступлением против его народа или другой социальной группы, к которой он принадлежит — отдельный болезненный вопрос. Особенно на постсоветском пространстве, где о репарациях или хотя бы освещении исторической правды пока не идет и речи.

Осмысление истории крымских татар ими самими — динамичный процесс, необходимый не только как вклад в массив исторических исследований, но и как способ сохранения жизненно важной памяти — исторической, народной и личной. Возвращение домой так долго было, а для многих до сих пор остается, мечтой нашего народа. Исторические исследования, которыми занимается Гульнара Бекирова — это возвращение голоса.

После аннексии Гульнара много путешествует по Украине, посещая конференции и читая открытые лекции об истории Крыма и крымских татар. Бекирова рассказывает, что благодаря аннексии она узнала о красоте и разнообразии Украины как страны. В последние годы она все больше занимается исследованием и популяризацией общей истории крымских татар и украинцев и их совместной борьбы с советским режимом.

В одном из своих интервью Бекирова отмечала, что звание профессионального историка «предполагает объективность и поиск исторической правды вне зависимости от национальной принадлежности». Она и сама при этом признает, что она — не только историк, но и крымская татарка, чья семья до сих пор не вернулась домой, и полное отстранение от политики или национального самосознания в таком случае невозможно. Как должна работать объективность исследователя, который занимается преступлением против его народа или другой социальной группы, к которой он принадлежит — отдельный болезненный вопрос. Особенно на постсоветском пространстве, где о репарациях или хотя бы освещении исторической правды пока не идет и речи.

Осмысление истории крымских татар ими самими — динамичный процесс, необходимый не только как вклад в массив исторических исследований, но и как способ сохранения жизненно важной памяти — исторической, народной и личной. Возвращение домой так долго было, а для многих до сих пор остается, мечтой нашего народа. Исторические исследования, которыми занимается Гульнара Бекирова — это возвращение голоса.

Меджлис крымских татар в России признан экстремистской организацией.

Gulnara Bekirova, Crimean Tatar historian

Alexander Murtazaev is a graduate of the Faculty of History at Erasmus University Rotterdam, a Crimean Tatar on his father's side. Telegram: @swellfella.

Seymor Nezoriy - Bachelor of Philosophy, graphic student in Kiev. Instagram: @nezoriy.

tags: Decolonization, Islam, Research, Indigenous Peoples, Racism, USSR, Ukraine

The history of Crimean Tatars, as of many other nationalities existing in the post-Soviet milieu, is one of unresolved conflict and pain. Only seventy years after the 1944 exile of Crimean Tatars from Crimea did Ukraine recognize the event as genocide. The event split life into a before and after for this ethnic group. The struggle for the right to return to their native soil continued well through the 1990’s, with many activists still fighting even today. The deportation and subsequent scattering of families, with communities and even ethnic subdivisions forming over the decades, led to an immense loss of historic material, access to oral tradition and familial history. The Soviet authorities attempted to reshape the historical narrative in a way that favored them. After the annexation of the peninsula by Russia in 2014, the history of Crimean Tatars gained distinct politicization.

Under such circumstances, the study of national history or that of dissidence transcends the framework of academism, transforming into part of a movement which returns to its people the right tо grief, a voice, and identity – collectively, the right to national history. Historians who are engaged in this matter often encounter situations which require reevaluation of the standards of research objectivity. Today, as the history of Crimean Tatars and the repression against its people continue to be marginalized and misrepresented, it becomes difficult to distinguish where historiography ends and politics, activism and protection of human rights begin.

Under such circumstances, the study of national history or that of dissidence transcends the framework of academism, transforming into part of a movement which returns to its people the right tо grief, a voice, and identity – collectively, the right to national history. Historians who are engaged in this matter often encounter situations which require reevaluation of the standards of research objectivity. Today, as the history of Crimean Tatars and the repression against its people continue to be marginalized and misrepresented, it becomes difficult to distinguish where historiography ends and politics, activism and protection of human rights begin.

Gulnara Bekirova is a historian who has worked on the intersection of these domains for her entire career. It would have taken three such articles to list all her scholarly publications, appearances on radio and television, partnerships with kindred organizations and other achievements. However, it nevertheless would not be enough to convey the immense scope of the researcher’s work. The Crimean history expert Bekirova’s practices can be divided into two key research paths: the first being the national movement of Crimean Tatars, its origins, development, peculiarities and principles; the second - the deportation of Crimean Tatars, the reasons behind it, its genocidal nature and its destructive consequences. Gulnara’s parents, Tasim and Kaside Bekirov, are originally from the Crimean cities Baidar and Kerch’. In 1967 they settled in Melitopol, where a year later Gulnara was born. Neither Tasim nor Kaside could return to their birthplaces after their deportation from Crimea: the territory of Baidar was partially closed off and inaccessible to Crimean Tatars, and their native village Anzhimendi near Kerch’ had been destroyed.

Bekirova recalls how in her school days, history didn’t interest her. Instead, what drew her in more was painting and fiction literature. Gulnara had even applied to Kharkiv State School of Art, but changed her mind and withdrew her application. Deciding on a profession did not come easy for Bekirova. After graduating from school, she worked as an operator at the Melitopol Motor Plant, thus giving herself more time to think. Her plans included the faculty of philosophy and the faculty of directing at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, continuing with two unsuccessful attempts to join the classics division at University of Leningrad, and an undershot of points for the faculty of history at Moscow State University. Finally, in 1989 Gulnara was accepted to the Moscow State Institute for History and Archives and graduated in 1994 with the specialty of historian-archivist. In 2003, she was accepted as a member of Memorial, part of the National Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, with whom she had been in contact with since 1996, if not earlier. This occurred after the publication of her article, “The problem of emigration of Crimean Tatars in Russian historical literature” in the collection Grassroots which had been created with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, together with Memorial. Already in 2008 she had left Memorial, which was quite a significant event for her – that year, she started her professorship at the Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University in the Department of History and Philology, and started hosting her weekly program Tarikh Sedasy (tat. – Echoes of the Past) on the Crimean Tatar television channel ATR, where she discussed important events and figures in Crimean Tatar history. Bekirova also hosted another program on ATR: Tarikh Levkhalari (tat. – Pages of History).

In 2012 Gulnara became a candidate of political science. She received her qualification at the I.F. Kuras Institute of Political and Ethnic Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. In a 2006 interview on the weekly show “Peninsula”, she remarked that her dissertation did not serve as an important milestone in the development of her career, and found no interest in it. “I value the essence and substance of a piece of work more than its form. That’s where my work lies,” Bekirova stated. It’s worth noting that the interviewer was the editor of “Peninsula” Vasvi Abduraimov, who is currently the chairman of the Crimean Tatar organization Milli Firka, the political opponent of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, with whom Bekirova collaborates. It’s noticeable: in the significantly long period between Gulnara’s graduation from university and earning her PhD, she managed to make a name for herself as a historian, publish numerous articles and monographs, participate in research projects and television programs, and receive the international B. Çoban-Zade Award, which recognizes outstanding humanitarian research on the subject of Crimea and artistic works in the Crimean Tatar language.

Bekirova recalls how in her school days, history didn’t interest her. Instead, what drew her in more was painting and fiction literature. Gulnara had even applied to Kharkiv State School of Art, but changed her mind and withdrew her application. Deciding on a profession did not come easy for Bekirova. After graduating from school, she worked as an operator at the Melitopol Motor Plant, thus giving herself more time to think. Her plans included the faculty of philosophy and the faculty of directing at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography, continuing with two unsuccessful attempts to join the classics division at University of Leningrad, and an undershot of points for the faculty of history at Moscow State University. Finally, in 1989 Gulnara was accepted to the Moscow State Institute for History and Archives and graduated in 1994 with the specialty of historian-archivist. In 2003, she was accepted as a member of Memorial, part of the National Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, with whom she had been in contact with since 1996, if not earlier. This occurred after the publication of her article, “The problem of emigration of Crimean Tatars in Russian historical literature” in the collection Grassroots which had been created with the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, together with Memorial. Already in 2008 she had left Memorial, which was quite a significant event for her – that year, she started her professorship at the Crimean Engineering and Pedagogical University in the Department of History and Philology, and started hosting her weekly program Tarikh Sedasy (tat. – Echoes of the Past) on the Crimean Tatar television channel ATR, where she discussed important events and figures in Crimean Tatar history. Bekirova also hosted another program on ATR: Tarikh Levkhalari (tat. – Pages of History).

In 2012 Gulnara became a candidate of political science. She received her qualification at the I.F. Kuras Institute of Political and Ethnic Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. In a 2006 interview on the weekly show “Peninsula”, she remarked that her dissertation did not serve as an important milestone in the development of her career, and found no interest in it. “I value the essence and substance of a piece of work more than its form. That’s where my work lies,” Bekirova stated. It’s worth noting that the interviewer was the editor of “Peninsula” Vasvi Abduraimov, who is currently the chairman of the Crimean Tatar organization Milli Firka, the political opponent of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, with whom Bekirova collaborates. It’s noticeable: in the significantly long period between Gulnara’s graduation from university and earning her PhD, she managed to make a name for herself as a historian, publish numerous articles and monographs, participate in research projects and television programs, and receive the international B. Çoban-Zade Award, which recognizes outstanding humanitarian research on the subject of Crimea and artistic works in the Crimean Tatar language.

Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula affected Bekirova’s life, just as it has for many other Crimean Tatars. For some time still after the event, Bekirova continued teaching at the Crimean University, whereas now she no longer lives in Crimea. As of 2014 Gulnara keeps a column by the name of “Pages of Crimean History” on the site Krim.Realii (rus. – Crimea.Realities) of the Ukrainian PEN Center. Since 201 she holds the position of vice-chairperson of the Kulturai Commission of the Crimean Tatar People in the study of the genocide of the Crimean Tatars, and has been assisting the Prosecutor’s Office of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in the investigation of the genocide proceedings, procuring relevant documents and sharing those sources that are already in her arsenal. Investigation is a complex task, since Ukrainian legislation does not coincide with the standards of international law governing war crimes.

Gulnara has travelled extensively throughout Ukraine post-annexation of Crimea, attending conferences and giving open lectures on the history of Crimea and Crimean Tatars. Bekirova explains that it was thanks to the annexation that she discovered the beauty and diversity of Ukraine as a country. In recent years, she has been increasingly involved in the study and popularization of the shared history of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians and their joint struggle with the Soviet regime.

In one of her interviews, Bekirova noted that the title of ‘professional historian’ “connotes a certain objectivity and a pursuit of historical truth independent of national identity”. She herself admits that she is not only a historian, but also a Crimean Tatar whose family has yet to return home, for whom distancing herself completely from politics or national consciousness is impossible. The way in which research objectivity within the context of dealing with crimes upon one’s own people or upon another social group to whom one belongs should work is a separate, painful question, especially within this post-Soviet space, in which reparations, or at least the coverage of historical truth, are still far from being addressed.

The processing of the history of Crimean Tatars done by Crimean Tatars themselves is a dynamic process which is instrumental not only as a contribution to the bank of historical research, but also as a way of preserving vital memories – historical, cultural, and personal ones. Returning to home soil has been the dream of these people for so long, and for some, it is still an ongoing one. Historical research, such as the type that Gulnara Bekirova does, signifies the return of a voice.

Gulnara has travelled extensively throughout Ukraine post-annexation of Crimea, attending conferences and giving open lectures on the history of Crimea and Crimean Tatars. Bekirova explains that it was thanks to the annexation that she discovered the beauty and diversity of Ukraine as a country. In recent years, she has been increasingly involved in the study and popularization of the shared history of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians and their joint struggle with the Soviet regime.

In one of her interviews, Bekirova noted that the title of ‘professional historian’ “connotes a certain objectivity and a pursuit of historical truth independent of national identity”. She herself admits that she is not only a historian, but also a Crimean Tatar whose family has yet to return home, for whom distancing herself completely from politics or national consciousness is impossible. The way in which research objectivity within the context of dealing with crimes upon one’s own people or upon another social group to whom one belongs should work is a separate, painful question, especially within this post-Soviet space, in which reparations, or at least the coverage of historical truth, are still far from being addressed.

The processing of the history of Crimean Tatars done by Crimean Tatars themselves is a dynamic process which is instrumental not only as a contribution to the bank of historical research, but also as a way of preserving vital memories – historical, cultural, and personal ones. Returning to home soil has been the dream of these people for so long, and for some, it is still an ongoing one. Historical research, such as the type that Gulnara Bekirova does, signifies the return of a voice.

The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatars in Russia is recognized as an extremist organization by Russian government.